Building a GPS-Free Drone: Engineering Indoor Autonomy from Scratch

Building a GPS-Free Drone: Engineering Indoor Autonomy from Scratch

When you remove GPS from a drone, everything changes.

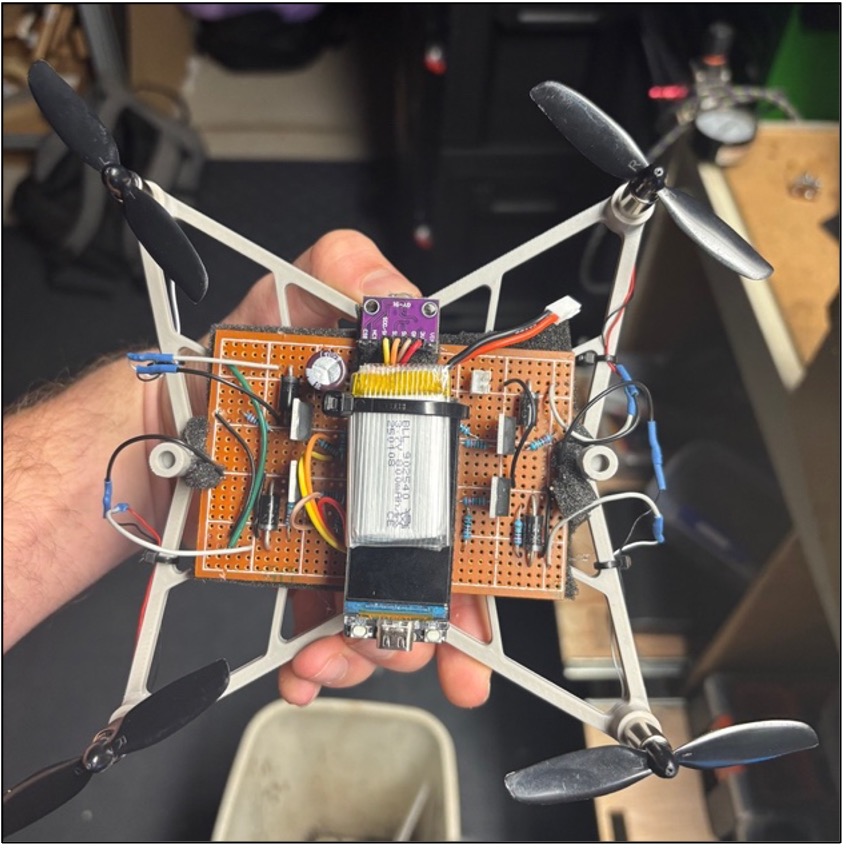

Our challenge in ELEC5552 was to design a safe, fully autonomous quadcopter that could navigate within a closed lab — no satellite data, no external positioning systems, and no tolerance for collisions. The result was a custom-built indoor drone that blends lightweight hardware, embedded control, and real-time sensor fusion into one cohesive system.

1. The Mission: GPS Denied, but Precision Required

Indoor operation means no GPS and unpredictable reflections off walls and floors.

Our goal: create a drone capable of hovering within ±0.1 m, detecting obstacles within 0.5 m, and navigating a predefined path for at least 3 minutes of flight time.

To achieve this, the design had to satisfy multiple constraints simultaneously:

Weight limit: < 250 g to meet CASA micro-RPA category.

Safety: software kill-switch and propeller guards mandatory.

Autonomy: operate purely from onboard sensors and control logic.

2. System Architecture: A Lightweight, Intelligent Core

We built around an ESP32-WROOM microcontroller on a custom 4-layer PCB, merging flight control, power regulation, and sensor interfaces.

Key subsystems:

Propulsion: 4 × 8520 brushed DC motors, PWM-driven at 18 kHz for quiet, smooth thrust.

Sensing: VL53L1X ToF sensors for altitude and obstacle detection, and a PMW3901 optical-flow module for planar odometry.

Communication: a Wi-Fi-based web interface providing arming, live telemetry, and a watchdog-backed kill switch.

This architecture allowed closed-loop hover control and navigation with deterministic latency below 200 ms — essential for safety in confined spaces.

3. Chassis: From Overbuilt to “Light-but-Sufficient”

Early prototypes failed because they were either too heavy (aluminium torsion-box frame) or too flexible (thin carbon flat-plates).

Through five iterations, we landed on a 3D-printed ABS hybrid:

34 g frame weight,

tall motor mounts to reduce z-axis flex and IMU noise,

snap-fit assembly eliminating screws, and

modular bays for PCB and sensors.

Static vibration tests showed the final frame pushed structural resonance safely above the control-loop frequency — a critical fix for stable IMU readings.

4. Control & Navigation: Making Sense of Chaos

The hover controller runs at 250 Hz, reading orientation and altitude to maintain a “level-at-target-height” goal.

A state machine planner executes primitives like FORWARD d, ROTATE θ, and HOLD t, while continuously checking for:

Obstacle proximity (< 0.5 m)

Link latency (> 200 ms)

Battery or sensor faults

When blocked, the planner arrests motion, sidesteps, and resumes — a simple but robust behaviour set that made early demo flights safe and predictable.

5. Testing the Limits

Over 25 structured tests validated everything from PID tuning to power-rail temperature imaging.

Key results:

Drone achieved hover stability within ±0.15 m.

Obstacle detection reliable at 0.4–0.5 m range on all axes.

System successfully auto-disarmed on link loss (watchdog < 1 s).

Remaining challenges included fine-tuning lateral drift and improving onboard power regulation under full motor load — both slated for next prototype.

Conclusion: Lessons Beyond the Drone

Designing a drone without GPS taught our team more about systems integration than any textbook could. Every decision — from the PCB stack to PID constants — was an exercise in balancing physics, electronics, and software.

Future iterations will explore:

Brushless motors for efficiency,

USB-C charging,

and carbon-fiber chassis for lighter, stiffer builds.

This project reinforced a key engineering truth: autonomy isn’t about adding complexity — it’s about making every gram, volt, and line of code count.

If you enjoyed this breakdown or want to see similar system-level builds, visit Josh-Wong.me for more technical write-ups and project updates.